Another first for the pot industry: A licensed cannabis restaurant

Cannabis edibles are a growing segment of the market and are expected to reach $4.1 billion in 2022, combining Canadian and U.S. sales. In 2017, that figure was just $1 billion among the two countries. The segment is going to be key to the industry's long-term growth.

Restaurants haven't been able to take advantage of that growth since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has still not permitted cannabidiol (CBD) to be infused into food. While the FDA has held hearings on CBD, there's no indication that changes are coming anytime soon.

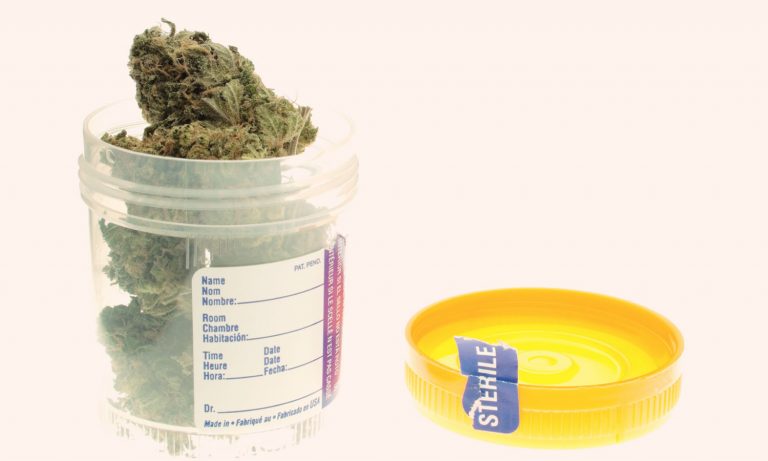

One restaurant, however, has been able to get around that problem. Lowell Farms opened its doors earlier this month in West Hollywood, Calf., and it's the first restaurant with a lounge licensed for cannabis use. Customers will be able to eat food and consume pot at the same establishment. That doesn't mean the restaurant will be able to make and serve cannabis food. Instead, cannabis edibles will be permitted only if they are "produced by an outside source."

One of the other restrictions the restaurant will face is not being able to sell alcohol to diners. It's a small price to pay to let them consume cannabis, since pot lounges remain a rarity in the industry. Las Vegas is among the cities looking at permitting such lounges, but that could be years away because there's still a lot of opposition to it.

Why lounges could be big for the industry

While marijuana has been legalized in many parts of the U.S., that doesn't mean it's possible to consume it at bars or sporting events, unlike alcohol where there are many places that users can drink in a social setting. Allowing that could unlock another avenue of growth for the industry.

Cannabis beverages are on the rise and expected to grow globally at a rate of more than 15% per year from now until 2025, reaching $4.5 billion in market size by then. So there's going to be a growing need for places to enjoy such drinks with friends without always having to do so at home. And that doesn't even factor in the growth of edibles that could be consumed at lounges, such as candy, cookies, and chocolate.

Growth opportunities for investors

Investors looking to tap into some of those opportunities may want to consider investing in Canopy Growth (NYSE:CGC). The cannabis producer is going to be a big player in the edibles market in Canada when edibles are launched. And it is among a select few in the industry that have a deal with a beverage company, Constellation Brands (NYSE:STZ). The two companies first began working together in 2017 when the beermaker first invested in the company. The two companies would likely see demand for their products soar if they could be consumed in lounges. While the Canadian-based company wouldn't be able to send its products across the border unless they're hemp-based, by the time cannabis lounges are common across the U.S, federal legislation may very well have been passed to legalize marijuana.

In Canada, there's potential for Canopy Growth to test its products in one lounge that was made legal earlier this year. In many ways, the emerging Canadian cannabis edibles market, which is going to be legalized later this month and where the first products will be available in December , could prove to be a good indicator of how successful some of these concepts will be in the U.S. And for Canopy Growth, it could be an important way to get closer to breakeven.

For now, Canopy Growth can be a good opportunity for investors to take advantage of the new edibles market in Canada. Not only is the company well-positioned for success in the beverages segment, but in a recent interview with BNN Bloomberg, CEO Mark Zekulin said the company was working on more than 50 different products for the edibles market. That could lead to significant growth for Canopy Growth and get investors excited about the stock once again.