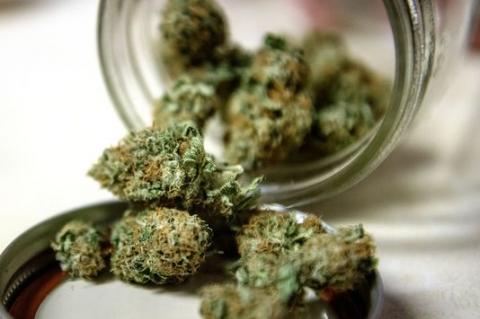

Slow rollout in marijuana sales costs Maine revenue and jobs

From legalization to legal sales, Maine is inching toward the slowest adult-use marijuana rollout in the U.S., with economists saying the three-year wait for stores to open will have cost Maine more than $82 million in taxes and 6,100 industry jobs.

The delay has caused some investors and industry experts to take their dollars and skills to other states, consultants say. Many of those who remain behind, committed to Maine, are spending cash they haven’t got to be ready for a market launch that is two years longer than average.

David Carr and Ray Payne have spent at least $750,000 waiting for that green light. That is what it took to lock down and hold on to the properties and personnel they will need to apply for the licenses required to open a recreational grow, manufacturing lab and retail store in Portland.

Ray Payne, left, and David Carr of Coast 2 Coast Extracts stand in their empty cultivation warehouse in Portland. The partners have been making lease, insurance and security system payments on the space they hope to use to grow marijuana once the adult-use recreational industry is cleared to launch. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

And because this is cannabis, a federally illegal industry without access to traditional banking, Carr and Payne have had to turn to private investors, incurring high-interest debt and handing over equity in the company, to float the business until they can even hope to start making money.

“We are going deeper into debt every day,” Carr said. “We are pretty lucky. We have investors who really understand the cannabis space. They understand the risks, the delays. A lot of people don’t. But it’s debt we shouldn’t have, you know? We’ll be paying for this delay long after we open.”

Maine voted to legalize adult-use marijuana in November 2016. After legislative rewrites, gubernatorial vetoes, and contractual snafus, state regulators are now saying Maine will record its first adult-use sales on March 15, or 1,223 days after voters narrowly approved full-scale legalization at the polls.

The seven states that legalized recreational marijuana use and sales before or at the same time as Maine – Colorado, Washington, Alaska, Oregon, California, Massachusetts and Nevada – required an average of 497 days from legalization to record their first sales.

Even Michigan and Illinois, which legalized adult-use marijuana in 2018 and 2019, predict their markets will launch before Maine’s. Illinois adopted its legalization law last July and is predicting stores will open on Jan. 1, 2020, making its 160-day rollout the fastest in U.S. history.

AN ECONOMIC PLAYER

Maine’s recreational cannabis market will top $158 million in sales its first year and almost $252 million in its second, according to economist Beau Whitney at New Frontier Data, a national marijuana research company that has studied legal and illegal market development in other legalized states.

These growth estimates are based on state population, marijuana consumption, medical marijuana sales and tourism trends, as well as the similarity of Maine’s proposed regulatory model with other markets. It assumes the black market will continue to serve 25 percent of total demand.

Using a conservative multiplier, where $1 spent is worth $2 to the economy, Whitney projects the adult-use market would have pumped more than $800 million into the Maine economy if the state could have pulled off an average rollout of 497 days instead of its 1,223 crawl to its first sale.

Based on Whitney’s projections, which have proven accurate in other markets, and the state’s tax rate of 20 percent, Maine could have made $82 million in marijuana taxes over those two extra years. That does not include other state taxes that would be collected, like payroll or income taxes.

Based on its projected size, New Frontier estimates Maine’s adult-use market will create 3,967 jobs in its debut year and 6,288 jobs in its second. These are plant-touching jobs only, like growers, chemists and retail clerks. The figures don’t include new indirect jobs, like accountants, security or human resources.

The average wage in the cannabis industry is about $17.50 an hour, or $36,400 a year, but that includes management positions and highly technical jobs requiring advanced degrees, like chemists. Most jobs in cannabis are relatively unskilled positions averaging between $12.50 and $15 an hour.

During the two years the adult-use market could have been generating profits and creating jobs, Maine’s medical marijuana industry is likely to have taken a hit, however, losing 12 percent of its sales and about 69 jobs, according to Whitney’s estimates. Overall, however, that would still be a win in terms of dollars.

But faster does not always mean better, especially when it comes to marijuana, said Scott Gagnon, head of AdCare Educational Institute of Maine, director of the New England Prevention Technology Transfer Center and member of Maine’s soon-to-convene Marijuana Advisory Commission.

“Never a bad thing to not be in a rush to add a new commercial industry that sells addictive substances,” Gagnon said. “Rush to commercialization hurt states like Colorado and Washington, as it led to issues with youth use, impaired driving and youth access to potent marijuana edibles.”

He would have liked to see the advisory commission begin to meet sooner – it was created in 2018 when state lawmakers overrode Gov. Paul LePage’s legalization veto, but is meeting for the first time just this week – but is hopeful it still has the time to take steps to mitigate these public health issues.

“Now that the industry will be coming on line, I hope we will have robust and productive conversations to ensure we do everything we can to protect our youth and communities,” Gagnon said. “This must take priority over issues of profits and revenues.”

People disagree on the desirability of the delay, but most agree on the reason: former Gov. LePage.

“Maine has really been a bummer, and that bummer has a name: Paul LePage,” said Nic Easley, the CEO of 3C, a national marijuana consulting firm with clients in Maine. “You could have been the first in New England to legalize, but LePage handed all that money, all those jobs to Massachusetts.”

Easley said he knew several entrepreneurs who had considered Maine for business partnerships and investments and opted instead for Massachusetts, a larger state that legalized at the same time as Maine but went live in 2018. Some may return to Maine when sales start, but some are gone for good, he said.

“Who knows exactly what LePage cost you?” Easley said.

RELUCTANCE IN AUGUSTA

LePage was a staunch opponent of adult-use marijuana sales. He campaigned against the referendum question, then vetoed two post-legalization bills. Even after legislators overrode his veto, his administration did nothing to begin the process of writing regulations or licensing the industry.

LePage could not be reached for comment and didn’t respond to attempts to reach him through a former spokeswoman who now works at his public policy group and a former senior political adviser who is now a Washington, D.C.-based Republican political strategist.

There’s more to it than LePage, of course. The referendum in Maine had the smallest margin of victory – 51 to 49 percent – of any state that legalized adult-use sales. And Mainers who want marijuana can get it, either from the robust medical market or a long-lived black market, so there’s been no real public outcry.

Even Maine’s cannabis community was divided over legalization – many medical marijuana growers and patients worried it would spell the end of their market – so politicians didn’t feel overwhelming pressure to deliver on a question that lacked unanimous support among marijuana consumers.

Other states that legalized marijuana with governors who opposed it at the time managed to enact adult-use sales in spite of it, with the likes of Massachusetts’ Charlie Baker and Colorado’s John Hickenlooper eventually turning the people’s will into a reality.

Although LePage never publicly said “not under my watch,” he vowed not to move ahead with adult-use sales until Maine was ready, while doing very little to make that happen. Even after lawmakers overrode his veto, LePage hired no consultants, wrote no regulations, made no staff hires.

“The difference in Maine was you had a governor who just didn’t want to do it,” said Andrew Freedman, Colorado’s former marijuana czar who is now a consultant who has advised Maine on its adult-use rules. “If you’re a governor, you can just kick the can down the road if you want. That’s what he did.”

Matt Simon, the New England political director of the Marijuana Policy Project, said it is only natural to compare Maine and Massachusetts, two New England states that legalized cannabis on the same day. It took Masssachusetts 742 days to log its first adult-use sale, the country’s second-longest launch.

“The rollout in Massachusetts has been frustratingly slow in comparison with most of the West Coast states, but the process has certainly gone much more smoothly and quickly than in Maine,” he said. “It all comes back to Maine having a governor who persistently refused to accept the will of the people.”

According to Greg Huffaker, the director of client services at Canna Advisors who has advised marijuana clients in 40 states and countries, LePage’s anti-marijuana position outdid even former Florida Gov. Rick Scott, who tried every trick in the book to block expansion of that state’s medical cannabis program.

“Some states launch their marijuana programs at the direction of their voters and fix the problems when they come up,” Huffaker said. “Other states, like Maine and Florida, have executives in office that cite all the problems that could happen and say they want to fix them, when what they really want to do is stall.”

PLAYING CATCH-UP

That changed when LePage left office. His successor, Janet Mills, created the Office of Marijuana Policy in the Department of Administrative and Financial Services in February, just one month into her tenure, and began hiring consultants even before they had staffed the office.

The occupants of the new office don’t refer to LePage by name, but talk in terms of before and after a lot.

“I think there’s two different stories,” said Erik Gundersen, the marijuana office’s new director. “I think the ‘what’s taking so long’ is a history before the Office of Marijuana Policy. … Some work had been done, but we ended up having to backtrack on it.”

Under that scenario, Maine would roll out in just seven months, making it the fastest in the country.

Gundersen is proud of how much his office has accomplished in such a short time, and how closely it has worked with both other state agencies and the industry to develop sound state policies and regulations in record time. He hopes that brisk pace will allay any clock-watcher’s concerns.

“We understand people have been waiting a long time and there are a lot of money and small businesses that are waiting for this industry to roll out,” he said. “But at the same time, we have to make sure we do it right because we are still talking about an industry based around a federally illegal drug.”