In pursuit of big profits, hemp growers blaze a perilous new path in Northwest agriculture

Image Source: Farmer Don Kruger is growing hemp for the growing CBD market in the U.S. Here, he examines a flower on a 22-acre field he planted on Sauvie Island in northwest Oregon. (Hal Bernton / The Seattle Times)

SAUVIE ISLAND, Ore. — On a foggy November day, farm workers take clippers to a field of bushy green plants, snipping tops full of flower buds dotted with flecks of sticky resin.

By the end of the day, the cuttings dry inside a southeast Portland warehouse, hanging from tall plastic trellises like aromatic curtains.

This harvest from a 22-acre patch of land looks, feels and smells like marijuana. But this is hemp cultivated to produce cannabidiol, or CBD, increasingly popular in pills, tinctures, oils, rubs and foods. Though lacking a psychoactive punch, CBD also is in high demand as a smokable flower marketed online with names such as Paradise, Charlotte’s Sauce and Honolulu Haze.

If everything goes right, and that’s a big if, hemp can be a very lucrative crop.

Last year, a 1-acre patch could yield about $70,000, far more than even high-value fruit such as cherries or blueberries, according to Portland-based industry analyst Beau Whitney.

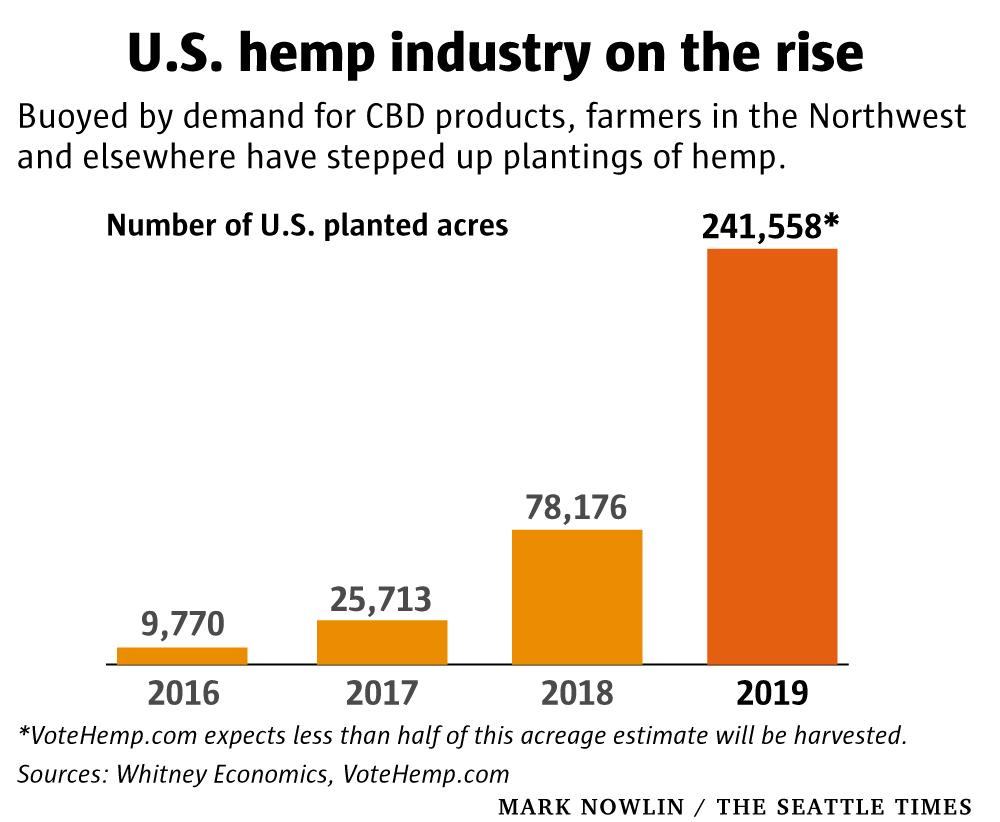

But hemp may require, even for a few dozen acres, a six-figure investment to bring the crop to market. And this year, farmers in Oregon, Washington and elsewhere are struggling with mold, poor seed quality, a scarcity of drying facilities and other problems that risk financial disaster to some. As they try to sell their crops, they find that a dramatic increase in U.S. plantings — and bottlenecks in processing — have pushed typical harvest prices down to $12,000 to $30,000 an acre.

“It’s a gold rush. Earlier in the season all people wanted to do was jam plants into the ground,” said Don Kruger, a vegetable and berry farmer who planted the island field northwest of Portland. “It was craziness, people were growing without knowing where it was going to go or who was going to harvest it… and got blindsided.”

There are unique challenges for farmers tending a crop that is the same species of plant — cannabis — as marijuana. The key difference as defined by federal and state laws is the level of tetrahydrocannabinol, a psychoactive compound known as THC, present in a plant.

Hemp farmers must pay for tests to ensure their plants do not exceed 0.3 percent THC. Above that, and their crop is considered to be marijuana that must be destroyed — even though that level is far below the 5% to more than 25% THC potency often found in cannabis crops grown for the drug markets.

So far, most Northwest hemp farmers have been able to meet the THC limit, according to Oregon and Washington state agricultural officials. But that hasn’t avoided all problems. One truckload of Oregon hemp was intercepted this year in Idaho by what state police called the “largest trafficking seizure of this type in any present-day trooper’s memory,” triggering a court battle that ended with a judge ordering the material returned to the shipper.

U.S. Department of Agriculture rules released Oct. 30 also, if not amended, likely will create problems for farmers in future harvests. They mandate tougher testing protocols for hemp, which will make it more difficult for farmers to stay within the 0.3% THC threshold.

“Most people will fail, so that [rule] is something we are hoping will change,” said Bonny Jo Peterson, director of the Industrial Hemp Association of Washington.

McConnell as hemp champion

Though hemp is new to this generation of U.S. farmers, the crop has deep American roots.

As far back as the 1600s, farmers sowed hemp strains that produced tall skinny plants with fibrous stalks used in rope, canvas sail cloth and many other products, including cooking oils and protein-rich seeds. In the 20th century, hemp fell out of favor, lumped in with marijuana, and subject to regulatory restrictions and eventually a ban. Only in World War II, when the Japanese invasion of the Philippines cut off vital hemp imports, did the U.S. Department of Agriculture exhort U.S. farmers to plant the crop.“American hemp must meet the needs of our Army and Navy as well as of our industries,” declared a 1942 U.S. government film, “Hemp for Victory.“

For much of this century, farmers could not legally grow hemp in the U.S. But in 2013, Congress gave approval for states to set up pilot programs for cultivating hemp. Then, in the 2018 farm bill, hemp was legalized nationally in a move championed by Sen. Mitch McConnell, the Republican Senate majority leader whose home state of Kentucky had once been a major producer of hemp fiber.

“We have merely scratched the surface of the countless benefits that come from this plant,” McConnell declared in a June 2018 floor speech. “Hemp will be a bright spot for our future.”

The surge

Five years ago, when state pilot programs gained congressional approval, Oregon developed some of the nation’s most hemp-friendly regulations, giving farmers more incentives to grow hemp as demand surged for CBD. In 2019, Oregon farmers registered to grow some 63,000 acres, a more than five-fold increase from a year earlier and one of the biggest acreages of any state in the nation.

There also is industry support to bolster hemp science at Oregon State University in Corvallis. A $1 million grant from a seed company this year launched the Global Hemp Innovation Center, which will draw upon the expertise of more than 40 researchers studying the plant in the U.S. and elsewhere. The center’s director, Jay Noller, who has done extensive research on hemp production in other countries, hopes Oregon farmers in the years ahead will give a greater emphasis to food and fiber production.

“They have gone too far toward CBD production. There are other ways to manage and grow it,” Noller said.

In Washington, the hemp industry has been slower to take off.

Initial state regulations for the pilot program were very restrictive. They forbid growing hemp for CBD during the first four years of the program, and few farmers grew the crop, with less than 150 acres planted in 2018.

This year, buoyed by new legislation at the state level greenlighting CBD hemp, interest in hemp cultivation surged. Farmers registered to grow some 6,000 acres.

Much of Washington’s hemp has been grown east of the Cascades, where large-scale fruit and vegetable production offers plenty of farm equipment, warehouse and other infrastructure.

“I’m optimistic we can get up to speed quickly,” said Robert Cook, co-founder of Columbia Valley Hemp Co., who oversaw 20 acres of hemp grown this year in the Tri-Cities area.

Cook says all of his company’s crops got out of the fields. But in Washington, as in Oregon, some harvests have been a struggle, and much of the hemp may never make it to market.

“If we could get 30%, I would be extremely excited about that,” said Peterson, the Washington hemp association director.

Risks play out

For some farmers who ventured into the resurgent hemp industry, the problems this season started early.

A Kentucky company, Elemental Processing, filed a September lawsuit alleging it secured 6.4 million poor-quality hemp seeds from Oregon-based HP Farms. Elemental distributed these seeds to Kentucky farmers, who ended up having to plow under their crops. The lawsuit seeks at least $44 million in damages, claiming the Oregon seeds were mostly males, rather than the “feminized” seeds promised by HP Farms and required to produce CBD.

HP Farms, in a response filed in Multnomah County Circuit Court, denied the allegations.

Kruger, the Sauvie Island farmer, opted to buy small plants that — while pricey at $1.50 apiece — proved to be good quality. Still his season has been a perilous roller coaster that often required big infusions of cash to grow, water, fertilize and harvest his crop.

Tensions peaked this fall as he tried to get his crops out of the field. After the farm workers cut the high-value flower, his plan called for a mechanical bean harvester, at a cost of more than $40,000, to come strip the leaves and other plant material that could be used for CBD extraction.

He eventually got two harvesters into the field. But he said one operator quit when he found a competitor sharing the job. He dumped some of the cut hemp on the ground as he made his exit, Kruger said.

By then, rain had caused more of the plants to turn brown.

“I know this should have been gone earlier,” Kruger said. “There’s been a huge deterioration.”

Once the crop was out of the field, there was more work to be done.

The fresh-cut hemp was high in moisture, and risked quickly turning into compost.

So, Kruger scrambled to find several other operations willing, at a price of more than $5,000 per acre, to run the hemp material through an intensive drying process.

Altogether, Kruger estimates he has invested more than $300,000. He has run short of cash and has plenty of uneasy moments.

But Kruger remains optimistic that he will make a profit from this crop. He hopes to grow hemp again next year.

- Log in to post comments